Long-Term Sobriety Is About More than Quitting Alcohol

It's about transforming your relationship with yourself

Thirteen years ago, I stayed sober for five years. I eventually relapsed for one reason: I failed to evolve. Sobriety is not a one-time event but, rather, a continual process of growth and development. This requires more than abstinence; it’s a complete change in identity and lifestyle.

The version of me in active addiction was wounded, insecure, unfulfilled, and spiritually destitute. That broken person would not only struggle to maintain long-term sobriety but be wholly uninterested in doing so.

During my current sobriety endeavor, I had to transform my entire self-concept to facilitate a radical shift in self-perception.

Accordingly, I embarked on a journey of self-discovery and renewal to reclaim my power.

Recently, I came across a quotation from life coach and bestselling author Brendon Burchard that perfectly encapsulates every stage of my journey. I use his words to describe how I gradually evolved from Chandni, the self-destructive abuser, into Chandni, the joyfully sober spiritual warrior.

First, it’s an intention.

Then it’s a behavior.

Then, a habit.

Then, a practice.

Then, it’s second nature.

Then, it’s simply who you are.—Brendon Burchard, High-Performance Habits: How Extraordinary People Become That Way

“First, it’s an intention.”

Based on its Latin etymology, an intention is more than a purpose or goal. It involves “stretching out” and “turning your attention to something.” Stretching out entails pushing beyond your comfort zone, and turning your attention implies changing your awareness.

It’s a conscious act of reorientation, and setting an intention is an essential first step.

Overcoming a long-standing fixation, such as substance abuse, demands repetition and discipline. For the newly sober, this can be an overwhelming challenge, which is why it’s crucial to set the right intention—a powerfully persuasive statement that personally motivates you.

During my first week of sobriety, people suggested the phrase, “I won’t drink just for today,” which was undoubtedly a logical, time-tested choice. In practice, it wasn’t convincing enough for me. As the weaponized instrument of my disease, my rational mind always countered with the same question, “Why shouldn’t you?”

I quickly recognized that in the trial for my sanity, my diseased mind was the prosecutor, the judge, and the jury. To survive future cross-examinations, I needed a genuinely persuasive answer to that question.

During subsequent rounds of inquiry, I had a solid response: “We deserve better.”

This added intention was compelling for several reasons. First, the pronoun “we” acknowledged my disease’s involvement, giving it a stake in the outcome. Second, the word “deserve” validated our worthiness. Third, the term “better” offered a plausible alternative to our current predicament.

My defeatist disease couldn’t believe we deserved happiness or fulfillment, but it accepted that we were entitled to improvement.

My mind now had a reason to look elsewhere. Through repetition, the intention went from being an empty proclamation to an authentic belief. Research shows that once a belief is established, the mind engages in confirmation bias by seeking evidence that supports it.

Suddenly, instead of seeking reasons to drink, I was seeking reasons to pursue something better.

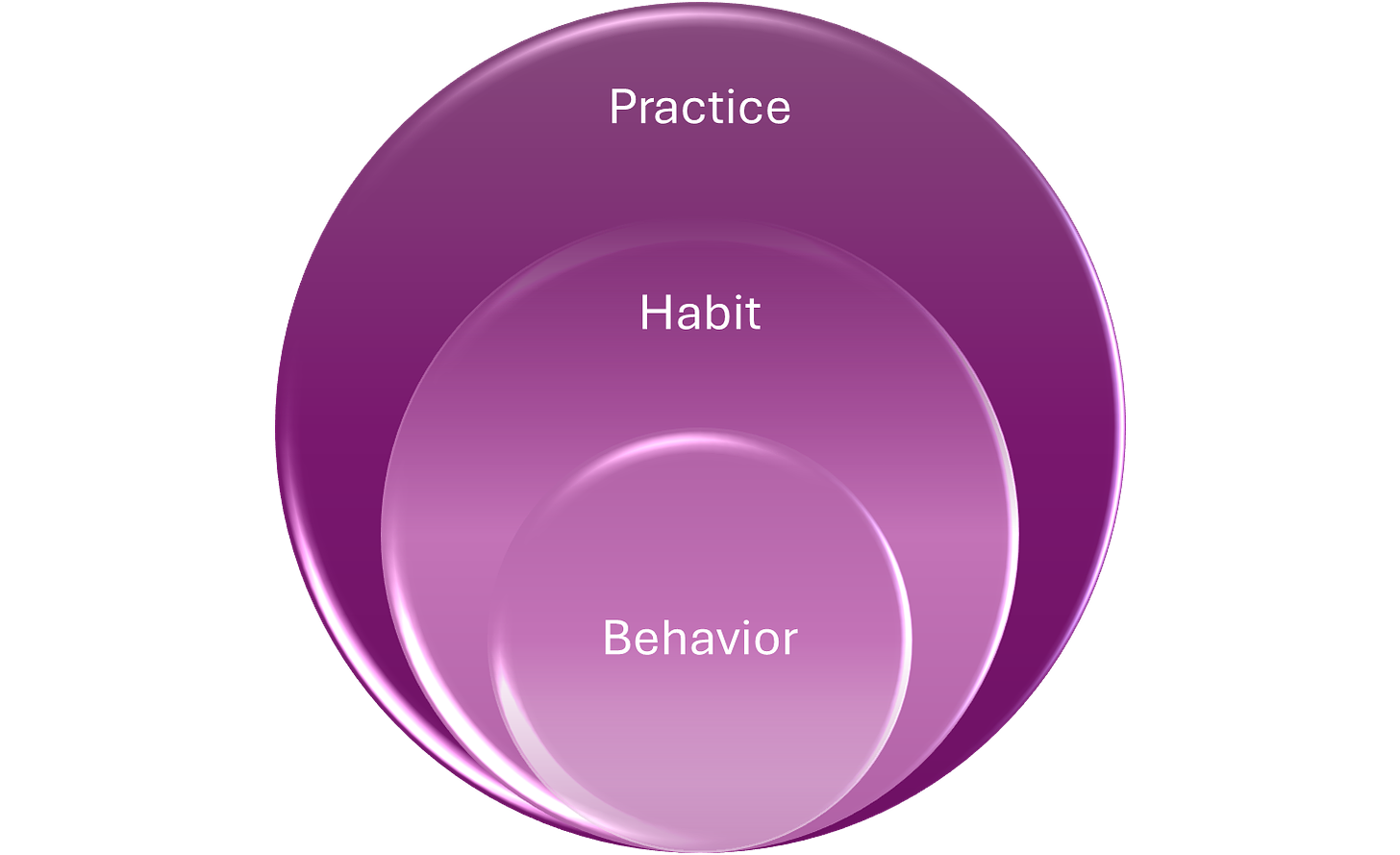

“Then it’s a behavior. Then, a habit. Then a practice.”

Often misused synonymously, behaviors, habits, and practices are distinct milestones in the identity change process. According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology:

A behavior is an activity “in response to external or internal stimuli.”

A habit is “a well-learned behavior or automatic sequence of behaviors that is relatively situation specific and over time has become motorically reflexive and independent of motivational or cognitive influence.”

A practice is “repetition of an act, behavior, or series of activities, often to improve performance or acquire a skill.”

Therefore, I needed to engage in habitual behaviors to establish an enduring practice.

Predicated on internal and external pressures, the behavior was easy to identify: not drinking. While compulsion was sufficient motivation to modify my behavior, it wasn’t enough to support a habit. I needed to internalize the activity without relying on the fear of negative consequences.

In his book Atomic Habits, James Clear charts a method for establishing and maintaining transformational habits to achieve a specific goal. Clear posits that bad habits are driven by craving and a need to change your internal state to alleviate discomfort. Once we associate a particular solution with even temporary satiation, we return to it regardless of its adverse effects.

To break a bad habit, Clear asserts that we must destroy its correlative relationship to relief by taking the following steps:

Make the habit unsatisfying.

Remove reminders of the habit from your environment.

Make it challenging to perform.

Focus on the benefits of avoidance.

To create a habit of not drinking, I removed alcohol from my environment, stopped associating with my former drinking partners, surrounded myself with other like-minded individuals, and focused on what I was gaining by not drinking.

I quickly realized that the habit I was actually trying to cultivate was not abstinence but consistently choosing my highest version of self.

This cognitive shift transformed my habit into a practice because self-improvement is a skill, not a destination, and practice makes perfect.

“Then it’s second nature.”

Clear emphasizes that realizing the benefits of a new way of life takes dedicated, persistent practice to produce meaningful, observable change and to traverse what he calls the Plateau of Latent Potential.

He states that to overcome this plateau, one must undergo three levels of change:

Changing outcomes (what you get)

Changing process (what you do)

Changing identity (what you believe)

For a practice to become second nature, we must achieve the first two levels of change.

When my focus shifted from abstinence to spiritual growth, I was getting not just more sober days but deep self-love.

I filtered all my activities through this specific lens until it became my default programming.

With this newfound growth mindset, I was no longer compelled to escape my emotional discomfort like during active addiction. I perceived my disquietude as something to transcend rather than evade. I learned to evaluate my emotional state with objectivity and used the insight to devise a strategy for spiritual progress.

“Then it’s simply who you are.”

The last of Clear’s changes, changing identity, is the most essential for not just creating but sustaining a transformation.

After years of devaluing myself, I finally established a lifestyle that challenged my old beliefs. I don’t just deserve better—I deserve the very best.

By changing my “I am,” I immediately shifted realities.

I am an evolving, divinely gifted soul.

I am a reality generator endowed with tremendous power and influence.

Alcohol and other substances don’t support this identity, so they have no place in my life. Once they lost all their value, I discovered all of mine.

The incredible aspect of the human spirit is its boundless potential. When you make reaching that potential your main goal, you start to align your life in a way that supports and nurtures that glorious vision.

You suddenly realize that you are the solution you sought externally.

You are the elixir of life. Bottoms up!

Well done!! As in TRULY! ❤️ I don’t drink (for 12 years) so I don’t struggle with that. What I DO struggle with is (for want of better words, said the writer 😜) those things that caused me to drink in the first place. One day at a time. Moved from AA to AAA— Awareness. Acceptance. Appreciation. Thanks again!

"...transforming your relationship with yourself." That says golden.